There can’t be many folk in Dolwyddelan who don’t know the legend of the American soldiers whose camp was flooded out at Roman Bridge, but not many know who these men were, and believe it or not, still are. We have Richard Swinford of Pen-y-Bont, Roman Bridge to thank, for his persistent research, leading to him uncovering the name of the regiment these GI’s belonged to. They were the 83rd Infantry Division, popularly known as the ‘Thunderbolts,’ hailing from Ohio. The unit was formed in September 1917 and travelled to war torn Europe in June 1918. They were mainly there as replacements for troupes that were being moved out, but a few of their units saw active service, taking part in the likes of the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in Italy.

The regimental badge, made up of the word Ohio.

In April 1944, under the command of Major General Robert C Macron, the Thunderbolts arrived in England, ready to undertake ‘on the ground’ training, in readiness for the D-Day landings; their main base camp being at Keele Hall, Staffordshire.

From there, troops headed out for rougher terrain, the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 331st Regiment belonging to the 83rd Infantry Division finding themselves in the landscape around Ffestiniog, the remoteness of the area allowing them to practice with live ammunition, without the danger of hitting anything but a few sheep.

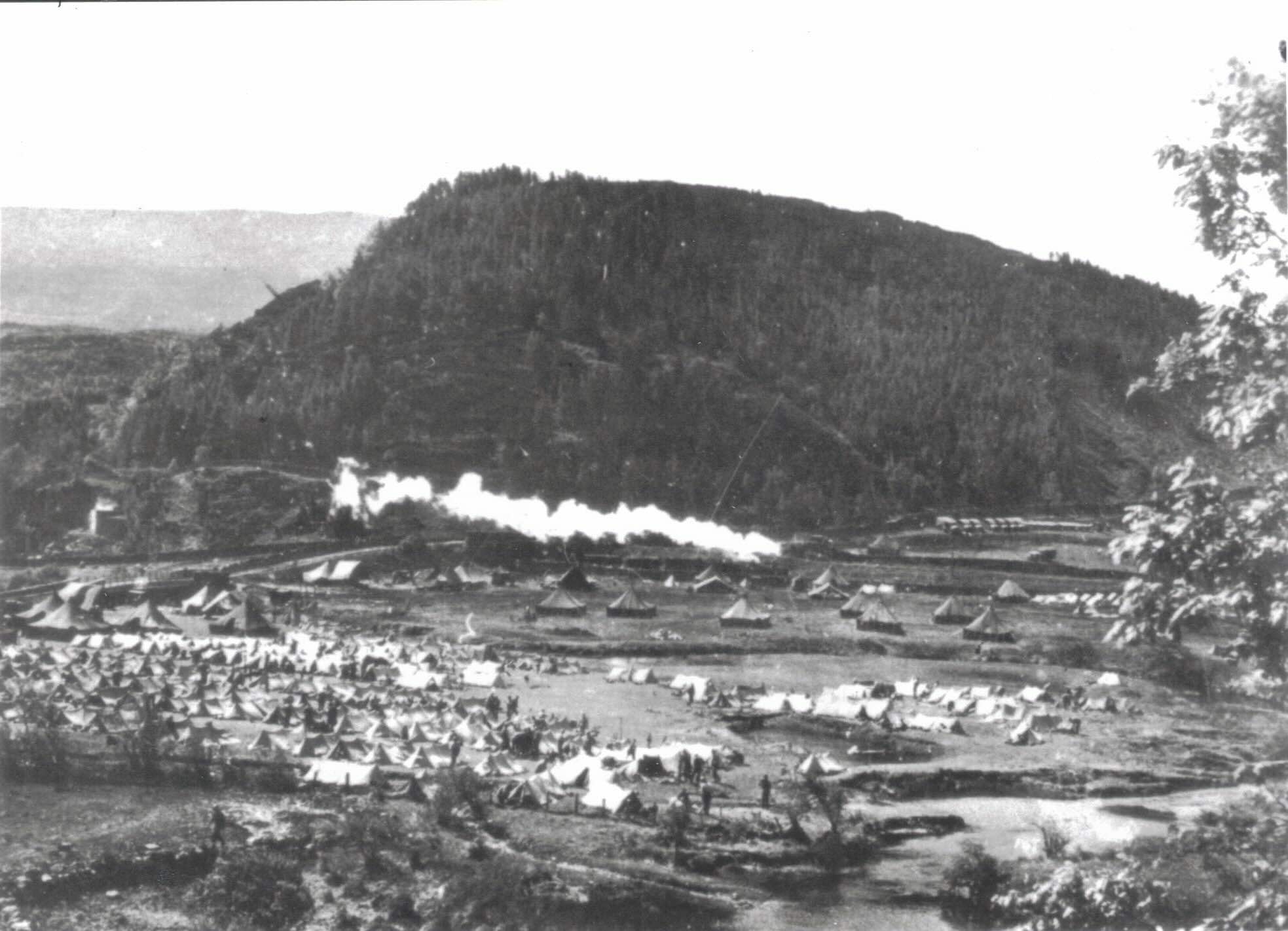

Much against the landowners advice, on the 10th of May, the Americans set up their base camp on the flat pastureland near the station in Roman Bridge. Anyone local knows this is a flood plain, but the GI’s didn’t listen; and this was not just a camp made up of a few tents, it was a small township of around 180 men, including mess tents, sleeping bivouacs, latrine blocks and stores.

All went well for a few days, the sound of gunfire echoing around the local hills. The men trained hard during the day and slept soundly at night with the help of the good Welsh air.

All was going well, or as well as training in a wet, freezing, wind blown landscape could go, until a few nights later, when further into the hills of Snowdonia torrential rain was falling. Along with the sunrise came a tidal wave of water, swelling the placid Lledr river, from a peaceful stream to a torrent, and then to a lake; the flood plain doing what a flood plain does! Within a very short space of time the whole camp was a foot deep in water, the sodden tents, along with the soldiers belongings were being washed downstream. A hurried evacuation was put into place, as many as possible taking the army vehicles which had been left overnight, on the road on higher ground, others getting on trains speedily laid on at the nearby Roman Bridge station.

From a local newspaper a few years after the event . . .

This was not quite the end. As the waters receded, all manner of desirable trophies were revealed. For a while, local youngsters enjoyed playing cowboys with real rifles (until the police took an interest.) Other souvenirs furnished local cottages, one lady still prunes her roses with fine-quality wire cutters abandoned by the Americans on that fateful night – still good as new in their original pouch. Many is the mantlepiece adorned with American bullets displayed proudly, or an American helmet being used as a feed bucket for the chicken’s corn.

The 83rd left Wales and headed for the south coast for the expected transportation to Europe, where they were to take part in the Allied Invasion of Normandy, but against all odds, the weather was again set against them.

These words are from the soundtrack of a Pathé Newsreel which shows the soldiers of the 83rd disembarking, in treacherous conditions and starting their advance into France . . .

‘A sudden channel storm whips up off the coast of Normandy. Off Omaha Beach lies the convoy carrying the 83rd, ships break up and run aground. Ashore the heavy steel landing piers are twisted and ripped apart. For three days and three night the division rides out the storm, waiting.’

They finally landed on Omaha beach on the 18th of June, less than two weeks after the allied D-Day invasion of Western Europe.

This is a first-hand account of what the men went through, only days after hastily departing Dolwyddelan . . .

England! We left her with mixed emotions. Some were glad the final period of training was ended, glad to get started in battle. Some regretted leaving England, kept remembering how Spring had grown full in May, kept remembering the peace in Midland villages on Sundays, the rain and mud in Wales, kept remembering the pubs, the inns, the girls. It was a little like leaving home again.

It was to have been short, that voyage across the Channel. Rushed through the staging areas near Stonehenge, the Thunderbolt Division had top priority in everything. The Thunderbolts were needed badly, in Normandy. The voyage was short in point of crossing. But we did not disembark. A storm rose out of nowhere and slashed at Omaha Beach and made life miserable for a week. We sat and stood and laid around on our ships. We sang songs, cleaned our weapons, used our vomit bags, ate our landing rations. We went down into the holds of the ships and drew more ten-in-ones. We steam-cooked and ate ten-in-ones until they were coming out our ears. And so, the days and nights passed.

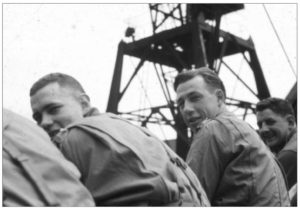

Men of the 83rd waiting to Land on Omaha Beach, just days after leaving Dolwyddelan.

And there were the sheer, forbidding cliffs of France, smack in front of us. Not two miles away. We wondered how in hell the D-day boys had managed them. All around us, to the horizon and beyond, were hundreds of other ships of the massive landing fleet. Scores of barrage balloons tugged with the wind, sometimes broke loose and floundered away. When the wind died down the muffled sound of gunfire could be heard. Some said it was fighting around Cherbourg. Others said it was around Caen. No one knew, really. None of us knew anything about battle. If you were positive about it during the day, like as not you’d change your mind at night. For then the sounds grew louder, and there were fires everywhere along the horizon, east and west. And Jerry was always overhead, raising hell with someone.

At first no one was sure about what to do during those raids. It became a question of going down into the bowels of the ship to escape the flak or staying on deck so if a hit was made you could jump into the water and swim for it. After a while, though, no one paid much attention. We grew impatient about landing. Anything would be better than sitting around in the Channel. Anything would be better than being part of this gigantic target for Goering’s Luftwaffe.

As soon as I had learnt from Richard Swinford which Battalion the soldiers belonged to, I of course did an internet search, and what do you know, the 83rd Infantry Division have a Facebook page. Late one evening I posted a message to them, asking if anyone had heard of the flooding at Roman Bridge, or knew anything about it; more in hope than expectation. The following morning I woke to a long series of replies, including . . .

Suzy Moravick – My father was in the rain and went to higher ground. My father who was an avid outdoorsman, told us the story and that he told the other men to get to high ground, but many did not.

Suzy Moravick – My father was in the rain and went to higher ground. My father who was an avid outdoorsman, told us the story and that he told the other men to get to high ground, but many did not.

Steve Moravick

Jodell Newman Ryan – My father said he was the coldest he’d ever been in his life in Wales.

Seimon Pugh-Jones – The greyest place on earth. Grey sky, grey stone . . . but the people with hearts of gold.

Judy Bielen – My father Stanley Bielen passed away in 2015. Amongst the memories he shared with his children was his regiments training in Wales around Mount Snowdon. He also related the flooding story.

Judy Bielen – My father Stanley Bielen passed away in 2015. Amongst the memories he shared with his children was his regiments training in Wales around Mount Snowdon. He also related the flooding story.

My father also spoke of how friendly and hospitable the locals were towards the GI’s.

Stanley Bielen was 19 years old at the time he was training in Wales

Tim Klu – Al Klugiewicz remembers training at Blaeneu Ffestiniog, he remembers the flooding and believes so much equipment was lost.

Tim Klu – Al Klugiewicz remembers training at Blaeneu Ffestiniog, he remembers the flooding and believes so much equipment was lost.

Aloysius Klugiewicz in Germany 1945

And here is Al, at a 102 and a half years old, in February 2019 at an 83rd reunion dinner.